While black history should be celebrated throughout the year and not just in February, the month provides the opportunity to not only recognize African Americans who have made significant contributions in the past, but also those who are presently making history. As there are numerous African American scientists and innovators who are typically celebrated during black history month in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM), there are also quite few African American scientists in modern times that are worth recognizing. One such scientist is Dr. Namandje Bumpus (pronounced Na-Mon-Jay), of The Johns Hopkins University. On Feb. 1, 2016, Dr. Bumpus granted an interview to discuss her background, the path to her current career, and potential avenues for under-represented minorities to get involved in STEM. I originally published this piece when I wrote for the Examiner, and two years later, I’m republishing here on my blog.

While black history should be celebrated throughout the year and not just in February, the month provides the opportunity to not only recognize African Americans who have made significant contributions in the past, but also those who are presently making history. As there are numerous African American scientists and innovators who are typically celebrated during black history month in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM), there are also quite few African American scientists in modern times that are worth recognizing. One such scientist is Dr. Namandje Bumpus (pronounced Na-Mon-Jay), of The Johns Hopkins University. On Feb. 1, 2016, Dr. Bumpus granted an interview to discuss her background, the path to her current career, and potential avenues for under-represented minorities to get involved in STEM. I originally published this piece when I wrote for the Examiner, and two years later, I’m republishing here on my blog.

Anwar Dunbar: First Namandje, thank you for this opportunity to interview you. My writings in February tend to focus on Black History Month and as a scientist myself I want to shine the light on other African American scientists and innovators who are currently in the trenches expanding our scientific knowledge. Also being in the biological sciences versus the information technology and robotics fields, it’s not so obvious to the lay person what a pharmacologist is, so for all of these reasons I thought about you. With those things being said, let’s start.

Talk a little bit about your background. Where are you from? Were there any scientists in your family who you were exposed to at an early age? Were you always interested in science? If so, was it always biology or were you good at other parts of STEM, mathematics for example?

Namandje Bumpus: I was born in Philadelphia, but grew up in western Massachusetts. There were no scientists in my family. I had an uncle who spent some time working in a lab as an undergraduate student. He wasn’t a scientist, but he still talked to me about how he enjoyed working in the lab. Hearing about his experiences working in a lab was interesting to me. Early on I liked chemistry. My parents and others in my family started getting me chemistry sets when I was in elementary school because I started vocalizing that I thought science would be something interesting to do.

I worked through them (chemistry sets) and I really liked it, and when I was ten (pre-email), I actually wrote a letter to the American Chemical Society to ask about information for careers for chemists. They sent me back lots of brochures and a letter discussing things you could do with a chemistry background. That really got me even more excited just having all of that information and starting to dream about the things that I would do. So I was really more chemistry focused until high school when I finally took a physiology class, and then realized that I wanted to lean more towards biology and physiology.

AD: Talk briefly about your educational path. We overlapped at the University of Michigan’s Department of Pharmacology. How did you get there? What got you interested in research?

NB: I went to Occidental College, a small liberal arts college and did some research there. We didn’t have many labs so I was doing plant research and I really liked that, but I thought that I wanted to do something that was more directly related to human health and physiology, so I started researching certain fields to see what that would be. I came across Pharmacology and it was something that seemed interesting, so the summer after my junior year, I applied for summer research programs in Pharmacology so I could try it out.

Michigan had a summer program called the Charles H. Ross Program for African American undergraduates to come and work in the Pharmacology Department for a summer, so I applied for that and I got it. That summer before my senior year, I had a really great experience in the department in general. I worked in Dr. Richard Neubig’s lab, and they gave us a short course where I was introduced to the principals of Pharmacology. That really sold me on Pharmacology and since I also had such a great experience in the department, I became really interested in going to the University of Michigan for graduate school.

Michigan had a summer program called the Charles H. Ross Program for African American undergraduates to come and work in the Pharmacology Department for a summer, so I applied for that and I got it. That summer before my senior year, I had a really great experience in the department in general. I worked in Dr. Richard Neubig’s lab, and they gave us a short course where I was introduced to the principals of Pharmacology. That really sold me on Pharmacology and since I also had such a great experience in the department, I became really interested in going to the University of Michigan for graduate school.

AD: Not a lot of people understand what doctoral training is like and what it entails. You chose the lab of Dr. Paul Hollenberg which was a Cytochrome-P450 lab and we will discuss that, but what was it like learning how to do research? For example, what was the question you were looking to answer through your thesis project?

NB: In my project I was specifically looking at how genetic variances and mutations that existed in the population could impact their ability to metabolically clear certain drugs that are used clinically. We focused on a drug used to treat depression called Buproprion, and we looked at an HIV drug called Efavirenz. So I was looking at how genetic mutations could affect clearance of the drugs, and how those genetic variances might impact different people having genetic differences in drug-drug interactions.

AD: So would that be in the area of Pharmacogenomics?

NB: Yes.

AD: So as a Postdoctoral scientist did you work on a similar project? Or did you go in a completely different direction?

NB: Yes, my postdoc was somewhat different. I was looking at how lipids and fatty acids are cleared and how we regulate that process. Specifically, I was trying to find which pathways in cells were responsible for the metabolism of fatty acids. In particular, we were interested in stress activated pathways and seeing how activation of these stress pathways impacted expression of Cytochrome P450s that were responsible for metabolism of lipids.

AD: So right now in your own lab, what are you all working on?

NB: Lots of different things. The major focus has still been P450s, but looking at two different areas. The first is seeing how P450s and their metabolites contribute to drug induced toxicities, and to see if there are ways we can mitigate toxicities. We’ve had a focus on drug usage through HIV. The other side of my lab has been helping in collaborative clinical teams to develop drugs for HIV prevention, and trying to figure out how people’s pharmacogenetic variances in drug metabolism can impact their therapeutic responses when they are taking drugs used for HIV prevention.

AD: Now just briefly, from your doctoral studies through your postdoc, were there skills that you had to develop or did you come ready to go with everything? What were your major learning points as you worked through your thesis and your postdoc?

NB: My postdoc was really different. The experimental tools that I learned during my dissertation didn’t really help with what I wanted to do in my postdoc. I wanted to learn something new. Obviously the thinking and knowing how to design experiments was translatable. In graduate school I was doing a lot of mass spectrometry, more chemical-type techniques, and more biochemistry and enzymology. In my postdoc I was doing more in vivo biology and physiology, so I was using mice for the first time. I had never worked with a whole animal before. So I had to do a lot of cell isolation experiments and injections, things I had never done before; so I really had to learn a lot of new techniques for my postdoc. Now in my lab its great because we’re able to combine all of that, so we do a lot of mass spectrometry, biochemical techniques, in vitro mechanistic stuff/enzymology, as well as a lot more whole animal work, and a lot more whole cell work, things that I picked up in my postdoc, and I was able to combine both skill sets to build my program.

NB: My postdoc was really different. The experimental tools that I learned during my dissertation didn’t really help with what I wanted to do in my postdoc. I wanted to learn something new. Obviously the thinking and knowing how to design experiments was translatable. In graduate school I was doing a lot of mass spectrometry, more chemical-type techniques, and more biochemistry and enzymology. In my postdoc I was doing more in vivo biology and physiology, so I was using mice for the first time. I had never worked with a whole animal before. So I had to do a lot of cell isolation experiments and injections, things I had never done before; so I really had to learn a lot of new techniques for my postdoc. Now in my lab its great because we’re able to combine all of that, so we do a lot of mass spectrometry, biochemical techniques, in vitro mechanistic stuff/enzymology, as well as a lot more whole animal work, and a lot more whole cell work, things that I picked up in my postdoc, and I was able to combine both skill sets to build my program.

AD: And you did your postdoc at?

NB: The Scripps Research Institute.

AD: Did you always have the leadership skills necessary to run a lab or did you have to learn them? Was it a work in progress?

NB: Yes, you always build on it and it’s still a work in progress. I think you don’t necessarily get trained for it in graduate school or as a postdoc, but I tried to participate in things that were extracurricular; the Association for Minority Scientists at Michigan, and in my postdoc I was a part of our postdoctoral association, so I tried to pick up leadership skills by being involved in those other groups; but even still you’re not prepared to run your own lab. You really learn it as you go; you try things to see how they work. You talk to senior colleagues to get their advice and potentially go back and try something else. You take mentorship or leadership classes which I’ve done too, but I think it’s always a work in progress.

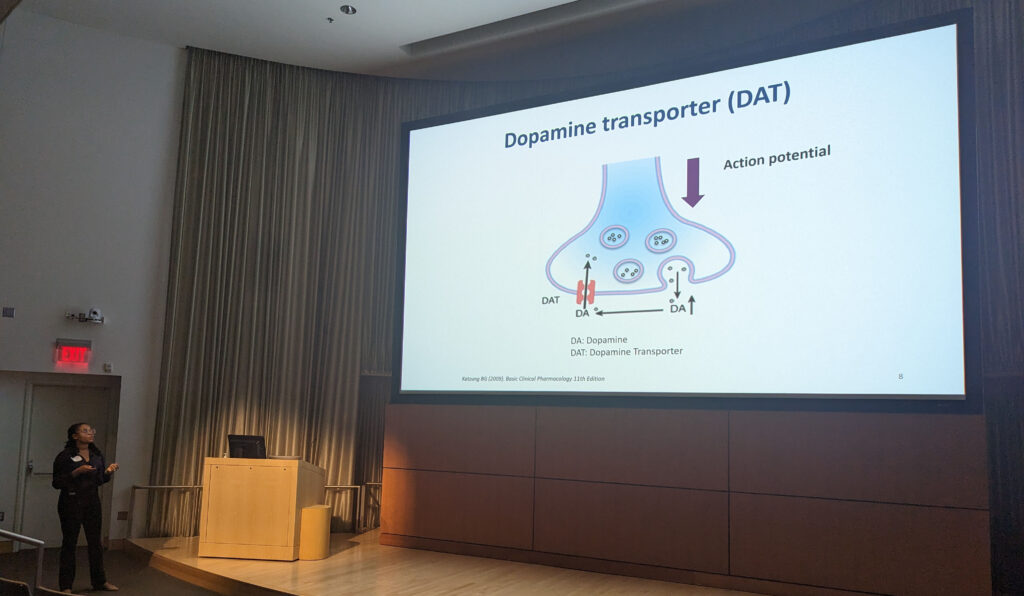

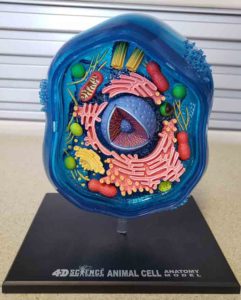

AD: We’re almost done. For the lay person, what are Cytochrome P450s and why are they important?

NB: They are proteins expressed in our bodies in all tissues, but mostly in the liver. What they largely help us to do is clear foreign compounds from our bodies. So for instance, if you are taking a drug therapeutically, you take it orally and you swallow it, one of the first places it’s going to go is into your liver. Your liver doesn’t want it to hang around and be inside of your cells forever, so we have these proteins that will change (biotransform) these drugs structurally to make them something that can be removed from your cells and removed from your liver. Thus, P450s are proteins that help us to clear foreign compounds and molecules. Drugs are obviously a large percentage of the foreign compounds that we’re exposed to, so we call them drug metabolizing enzymes.

AD: All of us went different routes after leaving Michigan. Some landed in the private sector in big pharma or the chemical industry. Others like myself, went into the public sector on the regulatory side, and I think I’m one of the only ones from our department to do that. A large chunk of our graduates went into academia which requires a ton of skills: leadership skills, entrepreneurial skills, and teaching skills. It’s also a very competitive environment and I very much admire my peers, such as yourself, who went that route. What made you decide to go into academia as opposed to the private sector or some other track?

NB: I think academia is the only thing that really fits my personality. I really like interacting with and training students. I like having a really close relationship with them where they come and work in my lab for several years while they work on earning a Ph.D. I get to see them grow. It’s similar with postdoctoral fellows. They come to the lab for a couple of years and I help them try to get to the next stage in their career.

I really love the educational aspect of the training. Additionally, I really like the broader training environment. In addition to my associate professorship, I’m also associate dean in the area of education where I get to spend a lot of time with graduate students who aren’t in my lab. I work more broadly with other graduate students helping them decide which lab they should choose for their thesis, and what they want to do next with their career. I further help them identify training opportunities for careers that they might want outside of academia. I really enjoy education training so this is the place for me.

Also, I like that scientifically, if I can dream it I can do it. If we have something that I really want to test in my lab, we can find a way to do it and test it out. I like the autonomy and the ability to be that creative with our science as well, so I think it’s a really good fit for my personality and goals.

AD: Now lastly, what advice would you give to young African American girls or those who are curious about science, but not sure that they can do it, or parents who are reading this and want to expose their kids to science?

NB: I think first knowing that if it’s something you really want to do, then you can do it. I think what’s most important about being a scientist is the passion for it and the interest. It’s not about everyone thinking that you’re brilliant. It’s about being interested and being a curious person and organically interested in science. I think it depends on which stage you’re at. If you’re in elementary school, starting off like me getting chemistry sets and microscopes is a good start – getting kids the type of gifts that will stimulate their interest and curiosity in science. Make them see that they do have the ability to do experiments and explore things on their own, and I really think that can get them even more excited about it. Microscopes, chemistry sets, and telescopes, those are things you start with from five years old.

Often times there are summer camps. At Johns Hopkins we have summer programs for people, middle school students and high school students. At many different stages you can contact local universities and museums to see if they have summer camps for science that kids can go to and that can be helpful. A lot of schools including ours have high school programs. In ours you can spend the whole summer working on a project and I think that’s a great way to see if you like scientific research and really get excited about doing research; so I think there are a lot of opportunities. You just have look out for them. The best place to start is contacting local universities and museums. Most universities will have a community engagement program you can contact for opportunities.

Often times there are summer camps. At Johns Hopkins we have summer programs for people, middle school students and high school students. At many different stages you can contact local universities and museums to see if they have summer camps for science that kids can go to and that can be helpful. A lot of schools including ours have high school programs. In ours you can spend the whole summer working on a project and I think that’s a great way to see if you like scientific research and really get excited about doing research; so I think there are a lot of opportunities. You just have look out for them. The best place to start is contacting local universities and museums. Most universities will have a community engagement program you can contact for opportunities.

AD: The last question, Namandje, involves something personal you shared with me. The science community recently suffered a great loss, someone who was a mentor to you. Would you like to say a few words in memory of this individual? From what I gather, this person was also a female African American scientist.

NB: Sure. Her name was Dr. Marion Sewer. She was a full professor at the University of California-San Diego, and a Pharmacologist as well. She worked on endocrinology and really did a lot to understand the endocrine system and how it impacts lipid metabolism.

She was just a very highly regarded scientist and she was also someone who cared a lot about outreach. She ran a lot of programs that were focused on diversity and giving opportunities for people in high school through undergraduate school, and really spent time with postdocs to make sure there were really opportunities for people of different backgrounds, including African Americans, particularly for African Americans to have exposure to science. She was someone who was a really great colleague, a really great scientist and someone who also, in a rare way, really cared about people, service, equity and inclusion in science. She really inspired me and helped me to get my first National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant by reviewing it for me several times. She was more senior and experienced, and I think a lot of us have that same story where she helped us get started because she was so generous with her time, so it was definitely a really big loss.

AD: Well thank you for this interview opportunity, Namandje, and your willingness to discuss your life and career. A lot of people will benefit from this.

NB: Thank you, Anwar.

Thank you for taking the time to read this interview. If you’ve found value here and think it would benefit others, please share it and or leave a comment. To receive all of the most up to date content from the Big Words Blog Site, subscribe using the subscription box in the right hand column in this post and throughout the site. Lastly follow me on the Big Words Blog Site Facebook page, on Twitter at @BWArePowerful, and on Instagram at @anwaryusef76. While my main areas of focus are Education, STEM and Financial Literacy, there are other blogs/sites I endorse which can be found on that particular page of my site.

While black history should be celebrated throughout the year and not just in February, the month provides the opportunity to not only recognize African Americans who have made significant contributions in the past, but also those who are presently making history. As there are numerous African American scientists and innovators who are typically celebrated during black history month in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM), there are also quite few African American scientists in modern times that are worth recognizing. One such scientist is Dr. Namandje Bumpus (pronounced Na-Mon-Jay), of

While black history should be celebrated throughout the year and not just in February, the month provides the opportunity to not only recognize African Americans who have made significant contributions in the past, but also those who are presently making history. As there are numerous African American scientists and innovators who are typically celebrated during black history month in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM), there are also quite few African American scientists in modern times that are worth recognizing. One such scientist is Dr. Namandje Bumpus (pronounced Na-Mon-Jay), of  Michigan had a summer program called the

Michigan had a summer program called the  NB: My postdoc was really different. The experimental tools that I learned during my dissertation didn’t really help with what I wanted to do in my postdoc. I wanted to learn something new. Obviously the thinking and knowing how to design experiments was translatable. In graduate school I was doing a lot of

NB: My postdoc was really different. The experimental tools that I learned during my dissertation didn’t really help with what I wanted to do in my postdoc. I wanted to learn something new. Obviously the thinking and knowing how to design experiments was translatable. In graduate school I was doing a lot of  Often times there are summer camps. At

Often times there are summer camps. At