Note. Like my Net Worth piece, the subject matter of this blog post is not new. It has been known for years by those who’ve learned about it in their families, learned about its concepts in business school, or who have discovered it on their own. It’s a discussion from my personal perspective which I think is worth visiting. Also, while this is a ‘money’ topic, I’m discussing it from a ‘scholarly’ perspective. I’m not rendering financial advice where I’m telling readers what they should do. In the spirit of the first principle of my blog, Creating Ecosystems of Success, I’m simply introducing a concept and discussing why it’s important for the lay person, so they can make their own life choices.

* * *

“Because we’re getting our Ph.D.s and we’re in school for so long, we won’t start making our money until much later,” my lab mate and senior graduate student Damon adamantly said. “When you save and invest your money, it doubles about every 10 years, and we’re missing out on the ‘doubling cycles’! The classmates I attended Colgate University with, who’ve already gotten out and started working, are already seeing their money double!”

“Because we’re getting our Ph.D.s and we’re in school for so long, we won’t start making our money until much later,” my lab mate and senior graduate student Damon adamantly said. “When you save and invest your money, it doubles about every 10 years, and we’re missing out on the ‘doubling cycles’! The classmates I attended Colgate University with, who’ve already gotten out and started working, are already seeing their money double!”

To start this off with some humor, coming from the eastside of Buffalo, anyone named Damon I’d ever met up to that point was black, but this Damon was of Greek descent. Damon was a very smart, opinionated and short-tempered guy. He was also knowledgeable on numerous topics: current events, politics, and economics, and I loved talking with him while in our research lab as I always learned something.

Damon introduced me to one of my current heroes, Dr. Thomas Sowell and let me borrow his copy of Inside American Education, which Dr. Sowell wrote. I didn’t know it, but that day while our Pharmacology experiments ran, Damon gave me my first lesson ever on the “Law of Compounding Interest”. I was in my late 20s, and similar to my learning about the ‘Net Worth’ and a ‘Matching Contribution’ concepts, it was late in the game, but still much earlier than many people learned about it. So, let’s talk about the Law of Compounding Interest and why we should all care.

As opposed to trying to piece together an explanation of Compounding Interest myself, I’m going to simply reference the book How To Turn $100 Into $1,000,000 which I referred to in my post entitled, Challenging misconceptions and stereotypes in class, household income, wealth and privilege. In that story I talked about how my mentor challenged me to read what appeared to be a children’s book. While it is written for children, the book contains lots of valuable information that many adults don’t have a handle on – even those in their 40s and beyond. Since reading the book I’ve consequently given copies to my younger cousins and other youngsters in my circle to give them the chances I didn’t have. You should too!

Before discussing the Law of Compounding Interest, I’m going to jump ahead to Chapter 9: Investing, because for the sake of this post, it needs to be introduced first. According to Chapter 9, investing is defined as, “Putting your money into something that can potentially make you more money.” There are likewise lots of investment classes out there: stocks, real estate, and businesses of all kinds.

Before discussing the Law of Compounding Interest, I’m going to jump ahead to Chapter 9: Investing, because for the sake of this post, it needs to be introduced first. According to Chapter 9, investing is defined as, “Putting your money into something that can potentially make you more money.” There are likewise lots of investment classes out there: stocks, real estate, and businesses of all kinds.

Coincidentally, the same buddy I discussed in my post entitled, We should’ve bought Facebook and Bitcoin Stock, recently approached all of us, looking for ‘investors’ because he wants to start his own Amazon store – a ‘speculative’ investment. When you think about the Law of Compounding Interest though, you want to think about putting your money in places where it will steadily ‘appreciate’ over time – someplace safe where you’d place your retirement savings for example (discussed below).

Two important concepts to understand here are ‘Principal’ and ‘Interest’. Financially, Chapter 8 assumes readers understand the meanings of Principal and Interest in the context of getting a ‘Return on Investment’ (ROI), as opposed to the borrowing context where you’re paying someone else interest on a loan. The chapter quickly starts discussing how Interest can steadily build your Principal from year to year.

If for example you have a $100 and it’s invested in something at a 5% interest rate after one year, you’ll have earned $5 so your total principal at the start of year two will now be $105. If you keep that $105 principal invested, it will earn the 5% on that amount and not the original $100, so your new total after year two will be $110.25, and so on. This is just an example, and this is just with the starting a principal of $100, but what if you started with a greater principal – let’s say $2,000, and you steadily added more money to it every month for 10-20 years? For retirement purposes the ideal scenario is to be invested for 40 years allowing one to retire well at age 65. Ideally the person should have started investing/compounding at age 25. However, getting started at any age is the key.

The second aspect of the Law of Compounding Interest discussed in the book is the “Rule of 72” on page 84. The Rule of 72 is a calculation which allows investors to determine how long it will take for their money to double based upon a given interest rate. To determine this number, you simply divide 72 by the interest rate that you expect to earn over time. The higher the expected ‘Rate of Return’, the less amount of time it takes to reach your goal. For example, if you divide 72 by an interest rate of 10%, it would take 7.2 years for your money to double. If you divide 72 by an interest rate of 2% the time would be 36 years – hence the importance of looking for the most competitive rate of return relative to your personal risk tolerance when looking for investments.

The chapter cites two more examples which highlight the importance of continuing to add to your principal and then the importance of time. The example on page 86 shows the difference in returns when two siblings both start with a $5,000 investment at the same age at an interest rate of 8%. One sibling continues to contribute to her account out to age 50 – that is $1,000 every year and arrives at 50 years of age with $750,000. The other doesn’t contribute anything further and arrives at 50 years of age with a total of $200,000.

The chapter cites two more examples which highlight the importance of continuing to add to your principal and then the importance of time. The example on page 86 shows the difference in returns when two siblings both start with a $5,000 investment at the same age at an interest rate of 8%. One sibling continues to contribute to her account out to age 50 – that is $1,000 every year and arrives at 50 years of age with $750,000. The other doesn’t contribute anything further and arrives at 50 years of age with a total of $200,000.

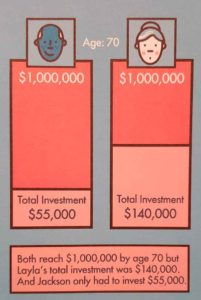

The last example on page 87 gives an example of two people who start investing at different times in life (pictured above). In this example both subjects become millionaires by 70 years of age. The first individual started saving $1,000 per year starting at age 15 and paid in only $55,000 to reach their $1,000,000. The second individual started at 30 years of age and had to put in a total of $140,000 to reach their $1,000,000. The take home lesson here is that because the first person started earlier, it took them less than half the principal of the second person the reach their $1,000,000.

* * *

My classmate Damon’s words at the start of this post, underscores these last two points. Our peers who started working immediately after earning their Bachelor’s degrees, were in theory able to start taking advantage of the Law of Compounding Interest earlier, assuming they knew to do so. Working towards our Ph.D. s, we wouldn’t be able to start the process until much later. But there were other professionals from our peer group who were getting even later starts than us due to the nature of their fields and the amounts of debt incurred during their educations; the Law and Medical students come to mind.

There’s another piece to this though. What about individuals who didn’t go the college route at all? They too would’ve been able to start using the law earlier in life assuming they knew about it and followed it. So, as I’ll describe below, having a degree has nothing to do with using this law.

Who should care about the Law of Compounding Interest? Everyone. That goes for STEM professionals like me and Damon, ‘Blue-Collar’ workers swinging hammers, cooks in the kitchen, lawyers in courtrooms, non-degreed individuals, business owners/entrepreneurs – everyone. No matter what your profession is, you only must know about the law, start it, and start it as early as you can.

To start using the law and to using it correctly, one must embrace two of the principles of my blog; the learning of Financial Literacy/Money, and Long-Term Thought/Delayed Gratification. Thus far in my writings I’ve discussed the latter principle sparsely, but it’s key here because to take advantage of the Law of Compounding Interest, the individual must think long-term. This means that they must be disciplined enough to live without a certain percentage of their paychecks every month.

They’ll also forgo or delay some short-term luxuries and indulgences for greater gains later – playing the game of ‘Chess’ in a way. This isn’t something that’s necessarily easy to do in the presence of considerable peer, societal, and in some instances familial pressures. See my Mother’s Day 2017 post, to get an idea of how to lose both money and time due to personal and cultural pressures.

They’ll also forgo or delay some short-term luxuries and indulgences for greater gains later – playing the game of ‘Chess’ in a way. This isn’t something that’s necessarily easy to do in the presence of considerable peer, societal, and in some instances familial pressures. See my Mother’s Day 2017 post, to get an idea of how to lose both money and time due to personal and cultural pressures.

What are the real-world applications for this? I’ll cite two articles. The first is by Rodney Brooks of the Washington Post. I cited his article entitled; 71 percent of Americans aren’t saving enough for retirement in my post about the Tax Reform and Jobs Act. It discusses reasons why people can’t take advantage of the Law of Compounding Interest. Another piece is entitled; Club Fed millionaire: Membership 23,000 and growing by Mike Causey which discusses the growing number of federal employees who are retiring as millionaires – most self-made. I’ll say it again, the majority are self-made meaning no one gave them anything, and they simply methodically prioritized, saved, and invested their money.

Of course, if you run a business, using a venture capital firm makes sense. Like investing, companies are also “money attractors”, but often more powerful. Using other people’s capital to get them off the ground can accelerate entrepreneurs along the path of compounding, just like it has countless times in the past for people like Larry Ellison and Elon Musk.

There’s a final context for the law, and that’s giving. When you think about Higher Education, philanthropists and generous alumni often leave gifts to their schools of choice through ‘Endowments’, many of which are invested so that they’re continuously compounding and generating returns used for scholarships and operating expenses. The famous Jim Kramer runs his “Charitable Trust” of which he is continuously thinking about out how and where to safely invest its funds for charitable purposes. Lastly, consider how the lives your relatives and your community could be changed by having a continuously growing principal and interest you can use in any fashion you see fit: saving up a down payment on a home, college tuition expenses, seed money for building businesses, supporting political campaigns, etc.

* * *

If it sounds like an underlying theme of this post and others like it is that your financial (and life) success is about what you know and don’t know (outside of your profession), then you’re correct. In an upcoming story I’m going to discuss how I didn’t understand these pieces when I first started my federal science career and didn’t take advantage the Law of Compounding Interest or the federal government’s ‘Matching Contribution’ – both of which have cost me money. There were actually several personal ‘blunders’ in these areas.

If it sounds like an underlying theme of this post and others like it is that your financial (and life) success is about what you know and don’t know (outside of your profession), then you’re correct. In an upcoming story I’m going to discuss how I didn’t understand these pieces when I first started my federal science career and didn’t take advantage the Law of Compounding Interest or the federal government’s ‘Matching Contribution’ – both of which have cost me money. There were actually several personal ‘blunders’ in these areas.

The opening quote for this piece is from the famous Physicist Albert Einstein and it pretty much sums up the importance of this topic – either you’re getting paid, or you’re paying out. Compounding Interest is something anyone can take advantage of regardless of: race, creed, color, sex, gender or religion. One just must know about it, and then start living by it. If they don’t know about it, they must be curious enough to find out about it. Most financial literacy programs cover it in some way.

There are other necessary pieces such as ‘Budgeting’ which I’ll cover as well in another post. As I stated in my Net Worth piece, it’s not something that can be worked out with your boss, or even legislated by the government, though I do think schools could do a better job of teaching this information at an early age. In closing, two other principles of my blog do tie in here, and they are Self-Accountability and Self-Reliance, because first, the individual must realize that no one can make them practice and incorporate this law into their lives, and secondly, it’s themselves who have to do it. And with that, I hope you’ve learned something here about the Law of Compounding Interest.

Thank you for taking the time to read this post. If you enjoyed it, you might also enjoy:

• Your Net Worth, your Gross Salary, and what they mean

• The difference between being cheap and frugal

• We should’ve bought Facebook and Bitcoin stock: An investing story

• Challenging misconceptions and stereotypes in class, household income, wealth and privilege

• What are your plans for your tax cut? Thoughts on what can be done with heavier paychecks and paying less tax

• My personal experience with Dave Ramsey’s Debt Snowball revisited

• Mother’s Day 2017: One of my mother’s greatest gifts, getting engaged, and avoiding my own personal fiscal cliff

If you’ve found value here and think it would benefit others, please share it and or leave a comment. To receive all of the most up to date content from the Big Words Blog Site, subscribe using the subscription box in the right-hand column in this post and throughout the site, or by adding the link to my RSS feed to your feedreader. Please follow visit my YouTube Channel entitled, Big Discussions76. Lastly follow me on Twitter at @BWArePowerful, on Instagram at @anwaryusef76, and at the Big Words Blog Site Facebook page. While my main areas of focus are Education, STEM and Financial Literacy, there are other blogs/sites I endorse which can be found on that particular page of my site.